Both of these examples illustrate the importance of sensing how effort applied translates to sound out. I think of this relationship as a Transfer Function: different amounts of energy in (effort applied) produce different changes in energy out (volume, roughly). When playing an unfamiliar piano, if you can build a mental model of this transfer function, you're more likely to be able to exploit its dynamic range effectively. It's also easier to avoid overplaying a piano whose sound is smaller than what you're used to or underplaying a piano whose sound is bigger.

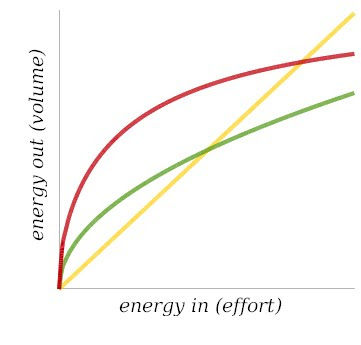

The graph below shows how energy out might vary depending on how much energy goes in for three hypothetical pianos.

The yellow curve is the transfer function for a hypothetical "linear" piano, where doubling the effort produces exactly double the volume over the entire dynamic range. The red line would be a piano where small changes in effort produce larger changes in volume at the soft end, but more effort is required to produce changes in volume at the loud end. For example, a small increase in effort (from a to b) might be required to go from pianissimo to piano, whereas a large increase in effort (from e to g) might be required to go from forte to fortissimo. The green curve represents the transfer function of some wacky imaginary piano where the louder it gets, the easier it becomes to play even louder.

The yellow curve is the transfer function for a hypothetical "linear" piano, where doubling the effort produces exactly double the volume over the entire dynamic range. The red line would be a piano where small changes in effort produce larger changes in volume at the soft end, but more effort is required to produce changes in volume at the loud end. For example, a small increase in effort (from a to b) might be required to go from pianissimo to piano, whereas a large increase in effort (from e to g) might be required to go from forte to fortissimo. The green curve represents the transfer function of some wacky imaginary piano where the louder it gets, the easier it becomes to play even louder.Real pianos would have transfer functions more like the red curve. Eventually, the curve flattens out to the right, meaning that as you hit the keys ever harder, you don't get much more volume.

The next graph shows how transfer function might account for differences in big pianos versus small pianos. One of the most surprising things when playing concert grands, for example, is how they continue to respond dynamically at the loud end. That is, even when playing loud, the piano has power to get even louder. The transfer function of smaller pianos flattens out faster than that of larger pianos. In the graph below, the red curve would be a larger piano, the green curve a smaller piano.

Any given piano may have a unique shape to its transfer function. The red curve in the graph below represents the transfer function for a piano that requires little effort to get from piano to forte, but then flattens out quickly. On such a piano, the risk to the player is in reaching high volumes with little effort, but then having no headroom left for louder passages. The tendency then would be to over-exert on loud passages, which can affect clean technique and result in fatigue. Keeping a model of this piano's transfer function in mind while playing would remind you that wide dynamic variation requires little change in effort in the soft and middle dynamic ranges, that forte comes easier than expected, and you should be careful not to hit the flat part of the curve before the loudest passages of the piece.

Any given piano may have a unique shape to its transfer function. The red curve in the graph below represents the transfer function for a piano that requires little effort to get from piano to forte, but then flattens out quickly. On such a piano, the risk to the player is in reaching high volumes with little effort, but then having no headroom left for louder passages. The tendency then would be to over-exert on loud passages, which can affect clean technique and result in fatigue. Keeping a model of this piano's transfer function in mind while playing would remind you that wide dynamic variation requires little change in effort in the soft and middle dynamic ranges, that forte comes easier than expected, and you should be careful not to hit the flat part of the curve before the loudest passages of the piece.